Sofie Berntsen’s new works in the exhibition Pasteller take a surprising diversion from the chilly elegance and “ruler–perfect” precision that we have come to recognize in her past exhibitions, Environment for expanded awareness at Kunstnernes Hus in 2007 and Skogen og Fjellet at Kunstnerforbundet in 2009. In these investigations, the artist unfolded a complex visual universe inspired by a conceptual interest in the scientific research process, and most importantly, it’s antithesis: the irrational experiences we have during our lives, and the mystery of the inexplicable that lies beyond the laws of physics. Berntsen’s work has taken form as astronomical concepts illustrated in linear diagrams; geometric and constructivist-inspired patterns; crystal objects displayed in glass cases; or dramatic and intricately detailed naturalistic scenes- all drawn with a thin pen and painstaking precision.

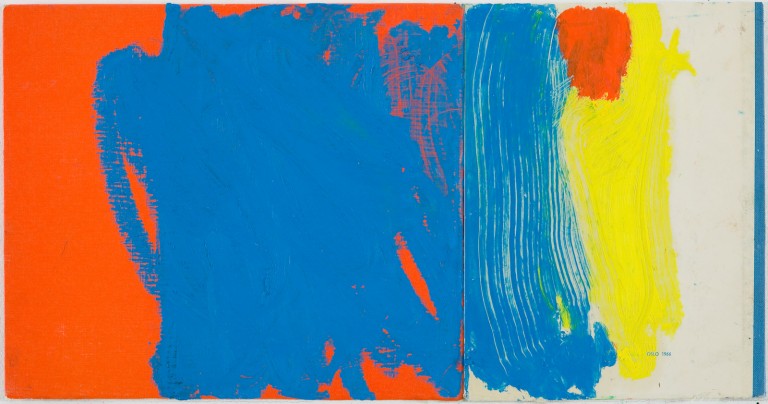

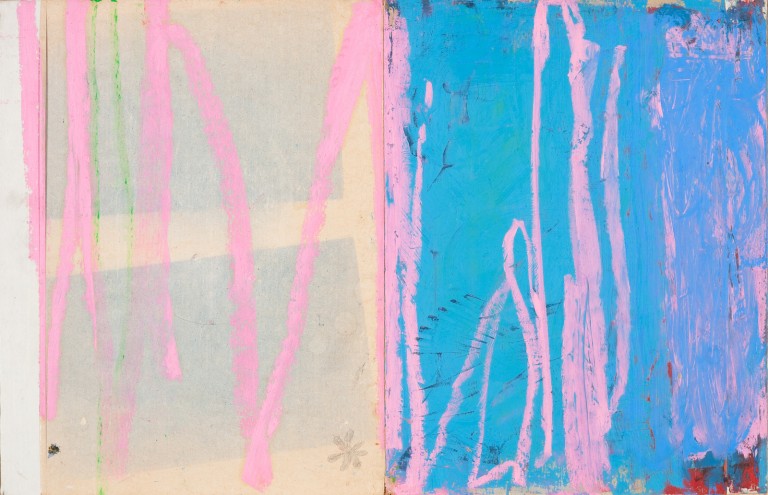

At first glance, Pasteller clearly investigates a different terrain. A collection of small oil-based pastels are painted on old book covers, some mounted on the walls, only a few actually in frames, and several are laid flat in two display cases within the gallery room. The books are a mixture of artist monographs, worn-out atlases, old school textbooks and something that seems to be a text in the book format of Albert Einstein. In this last work, the title is partly obscured by Berntsen’s controlled, but strong strokes with the pastel crayon, resulting that the English line of text “by” is erased and replaced by “for”, leading to the new interpretation: “An article for Albert E.”

To challenge the father of Relativity Theory is definitely not Berntsen’s intent. The gesture can be understood as a reflection on the experience an artist may have in confrontation with literary and traditional authority. It may also be interpreted as an appreciative recognition of the physics giant’s openness to acknowledging the creative and random forces at play even in the scientific investigation of the world. The material actions in Pasteller show a similar exploration of the potential freedom laying at the core of artistic process. The recycling of old materials in collage format can be understood as the artist’s search for security in the simple; in the most basic form of artistic creation. The apparently reckless and spontaneous application of color and loose form over the surface also bears clear references to modernist abstract painting, expressionism and painters such as Paul Klee, Hans Hartung, Ellsworth Kelly and Howard Hodgkin.

In similarity with the surrealists, the abstract expressionists investigated the unconscious and the irrational. In light of this, the physical gesture onto the canvas- the bodily movement in the artist’s stroke and the handling of the substance of paint- can be seen as echos of the soul’s labyrinth. Today it is not as easy to draw such clear conclusions between a formal expression and an authentic individuality and is not Berntsen’s project to revisit art historical directions. Although the leap from earlier work appears, at first impression, to be long, Pasteller is just as strongly motivated by the need to investigate the possibility found in the boundary between knowledge aesthetics, nature and an irrational and intuitive impulse. The coldly illustrative and academic qualities of the evocation of these themes are abandoned in Pasteller in favor for what we can call a liberation project, in both an aesthetic and more spiritual sense. At the end, it relates to the common principle of all artistic practice: the ability to follow an abstraction to a concrete form, and simultaneously make concrete forms and objects the bearers of abstract ideas. Or, as Albert Einstein himself formulated it: “imagination is more important than knowledge.”