Exhibition opening Saturday 26.04.2025, 12:00-16:00

The motifs of cross and drop – paint on canvas, aluminium and glass – are framed by two short silent films that speak of intimacy, care, longing, memory and love. All the work here by A K Dolven speaks to a sense of place that relies for its meaning on presence and existence which is itself both mystery and fact. The drop paintings are square in format, neither landscape nor portrait, whereas her cross paintings are oblong and adopt the proportions of a flag. These groups of paintings offer a challenge to the supposed objectivity and rationality found both in the square and grid and in a modernist illusion of purity located in the idealisations associated with the monochrome. These works cannot help but open up personal responses by the viewer in part because of the generosity invested in them by the artist.

The two film works – one presented as video on a monitor positioned at just above head height, the other a 16mm film projected on the wall – are short, looped narratives of loving relationship presented in terms of presence and loss. On the monitor, we see a head of blonde hair cradled by a pair of male hands. The anti-gravitational fall of the hair shows that the image is inverted. The camera is still, and the hair moves in occasional gusts of wind, gently moving like petals of a tulip caught in a draught. The work draws its title from a love poem by the Norwegian poet Stein Mehren: “I hold your head / in my hands, as you hold / my heart in your tender care / as everything holds or is / held by something else than itself ...” Through its simple image the film communicates feelings of vulnerability, and nurturing and supportive love.

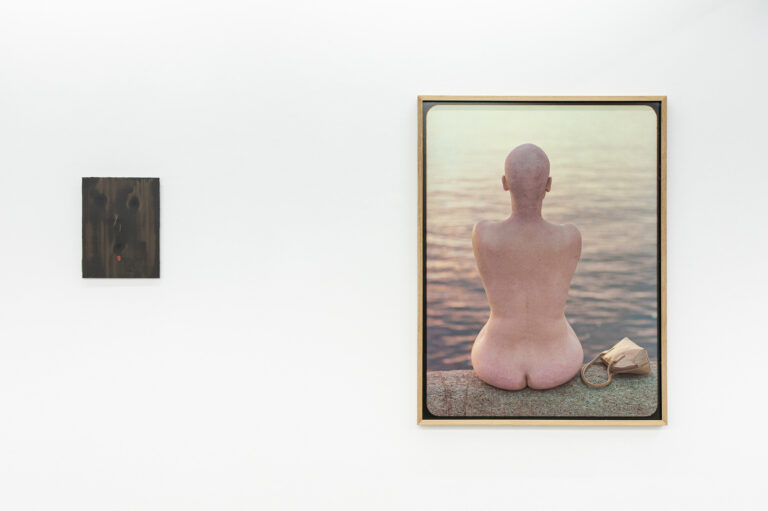

The embrace of I hold your head in my hands 1999 is answered by the other film, tilts only (his shirts) 2007, where we are faced with the evidence of a body that is no longer there. The small projected image, perhaps only slightly bigger than life size, shows an array of a man’s work shirts – plain, striped and check – hanging together on a rail. In a short sequence of close-ups, the camera tilts down the surface of the hanging empty shirts, almost seeming to caress and stroke them. The shirts that Dolven gathered for this film had belonged to her husband who had died a few years previously. In the words of Roland Barthes “every object touched by the loved being’s body becomes part of that body”. The slow meditative attention to the folds of the shirts and their sleeves – thinking of them being worn and enlivened but now hanging limp – constitutes a comforting and profound act of mourning and celebration of the man no longer there.

The edited sequence of repeated tilting looks down the shirts’ folds of printed fabric: plain against plain against striped against check. Shadows and stripes coalesce into a set of surfaces – what is figure and what is ground? In looking at its evolving narrative the film switches back and forth in our mind, becoming otherwise unremarkable garments that are by turns sexualised and memorialised through the quality of the lens’s gaze, and abstracted by the specifics of the film’s material, process and pictorial narrative: between the tilting of the heavy camera on its tripod and close- cropped panning of the resulting concentrated image. This is an abstraction that also relies on scale – domestic yet tragic – for its power. Dolven has related the painting of Barnett Newman to this film and the degree to which Newman’s work is built from a sense of place and a sense of being and becoming is certainly apposite. The title he gave to his breakthrough paintings of the late 1940s and early 1950s – Onement – speaks to this, as does his early annotation regarding these paintings in terms of ‘atonement’, being at one with oneself and others: repentance, renewal and beginnings. For Newman the encounter with his paintings for any viewer was about engendering a feeling of knowing you were there, and from which the force of his paintings could then unfold: “I hope that my painting has the impact of giving someone, as it did me, the feeling of his own totality, of his own separateness, of his own individuality, and at the same time of his connection to others”. Dolven’s work extends this through an attention to forms of collaboration. Her paintings are not a cross – a sign, flag or modernist badge – but indicate a meeting point, an exchange, an involvement of community. How a head held in your hands also suggests how everything holds or is held by something or somebody other than itself.

– Text by Andrew Wilson

A K Dolven (b. 1953) lives and works in Oslo and Lofoten, Norway. Dolven’s practice involves a variety of media; painting, photography, performance, installation, film and sound. Recurring themes in her production are the representation of natural forces and their resonance with human sensibilities. Her work alternates between the monumental and the minimal, the universal and the intimate. Interpersonal relations and interactions are central to her practice, and many of her performance-based works are collaborative.

Dolven has exhibited extensively, including Kunsthalle Bern; Philadelphia Museum of Art; Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin; IKON Gallery, Birmingham; Platform China, Beijing; The National Museum of Norway; KIASMA, Helsinki; CCC Tours, France; Louisiana Museum of Modern Art.

She is part of several collections, including The Art Institute of Chicago; Philadelphia Museum of Art; Arts Council Collection; Hoffmann Collection; KIASMA; La Gaia Collection; Goetz Collection; Fundacion Salamanca Ciudad de Cultura; Kunsthalle Bern; Küpferstichkabinett; Leipzig Collection of Contemporary Galleries; Louisiana Museum of Modern Art; Malmö Museum; The National Museum of Norway; The Museum of Contemporary Art, Denmark.

Andrew Wilson is editor of the Patrick Heron catalogue raisonné of oil paintings (for the Patrick Heron Trust, forthcoming 2027 by Art Publishing Inc.). A critic, historian and curator, he was previously senior curator of modern and contemporary British art, and archives at Tate Britain (2006-21) and before that had been deputy editor at Art Monthly (1998-2006). He has published and curated widely on many aspects of British and international art of the 20th century with a concentration on post-war modernist and countercultural currents, and is the author of Richard Hamilton Swingeing London 67 (f) (Afterall/MIT Press 2012). He is a founding fellow of the London Institute of ‘Pataphysics, and first wrote about the work of A K Dolven for the 6th International Istanbul Biennial in 1999.