Exhibition opening:

Thursday 21 November, 18–20:00

Curated by Dag Erik Elgin

Presenting:

Per Barclay, Camille Corot, Ángela de la Cruz, Dag Erik Elgin, Ane Mette Hol, Lawrence Weiner

Light is fundamental to us as humans, and naturally, we have been concerned with how the phenomenon can be explained physically and scientifically. But despite countless explanatory models, from the earliest scientific theories to the revolutionary principles of quantum mechanics, it seems that the physical nature of light still cannot be fully captured by the laws of physics.

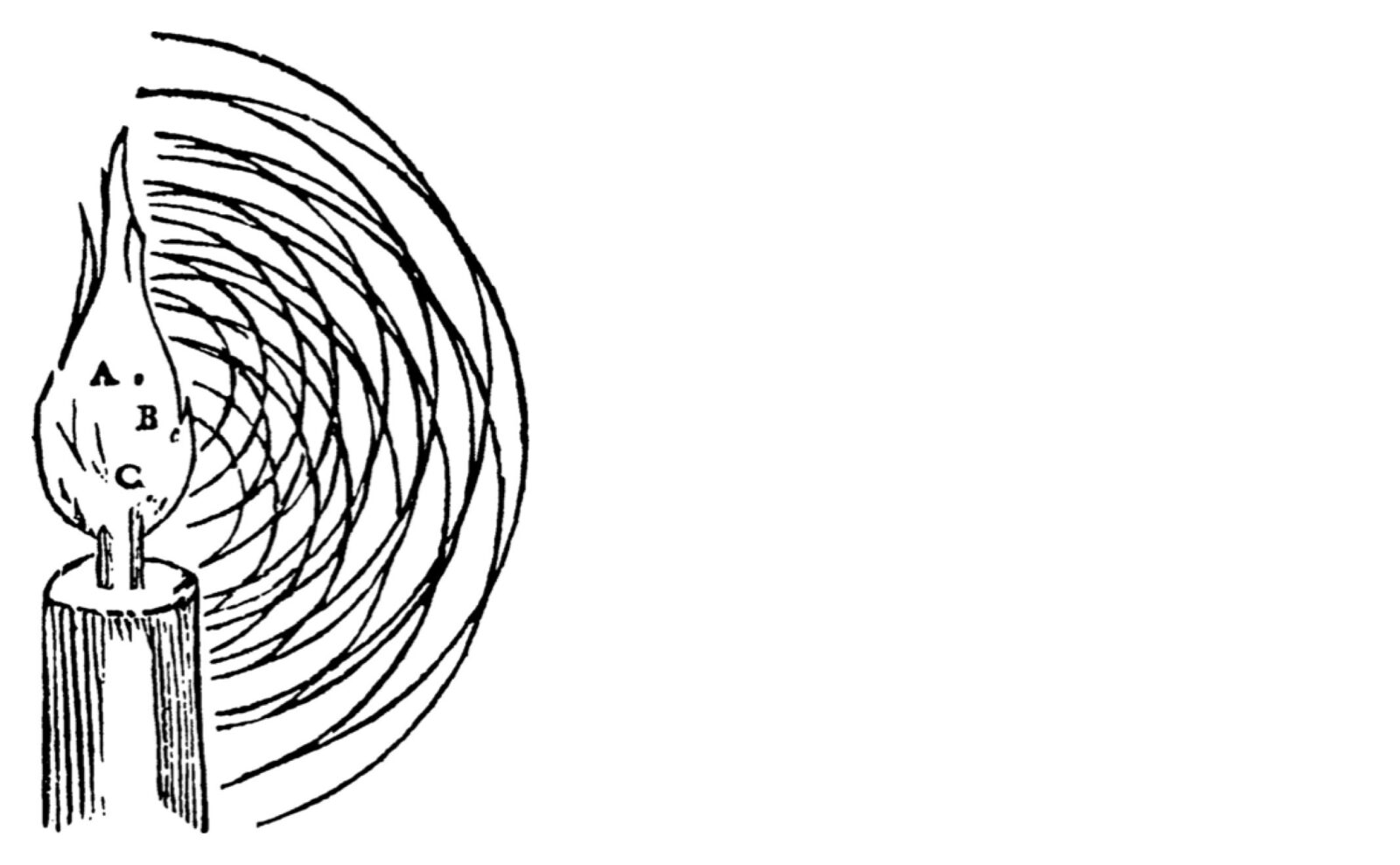

In the 17th century, a fundamental debate arose among physicists about the nature of light. In his Traité de la Lumière (1690), the Dutch mathematician and astronomer Christiaan Huygens (1629-1695) formulated one of the first theories describing the movement of light as waves. Later, Isaac Newton (1643-1727) claimed to disprove the wave theory through the so-called corpuscular theory, in which light is described as consisting of particles (Latin Corpusculae). Newton's theory was published in his groundbreaking work Opticks: or, a Treatise of the reflections, refractions, inflexions and colours of light (1704), based on the newly discovered laws of motion, where light is defined as the rectilinear and forward movement of corpuscles. Over two hundred years later, the fundamentally different theories of Huygens and Newton became precursors to quantum mechanics' so-called dual theory of light, where Albert Einstein proved that light can exist both as individual particles of energy and as waves, but that these two properties depend on the method of measurement and cannot be observed simultaneously. Thus, the originally conflicting theories of Huygens and Newton are harmonised in modern physics' understanding of the phenomenon of light.

Nearly three thousand years earlier, however, wave and mass (particle) were brought together in the Greek poet Homer's (900-800 BC) description of the goddess of dawn, Eos. Almost every song in the Iliad and Odyssey begins with the dawn of a new day in the form of Eos traversing the sky in her chariot, dressed in flowing saffron-coloured robes, gently tracing her rosy fingers along the horizon. In classical Greek poetry and mythology, dawn is personified, depicted against the sky in Eos' metaphorical wave-like motion as she prepares the way for her brother, the sun god Helios.

In addition to astronomy and mathematics, the scientist Christiaan Huygens contributed to the development of the microscope. When a completely new world was revealed under the optics he had developed, Huygens' reaction was to request an artist. He had discovered something that was without reference and not immediately accessible, which demanded visualisation of a landscape for future models of thought; that is, artistic formulations that transcend mere illustration. Art can also be illustrative, but its enduring contribution is interpretation, synthesising and formulating visual and poetic tropes that travel through the centuries, aesthetically articulating human and knowledge-based insights.

Art has a descriptive function in encountering natural phenomena, but its lasting impact is above all speculative in the expanded understanding of the word: in the artwork, what has not yet been formulated and has not fully emerged can be made visible. This can involve the contours of an image that has not been given a permanent form, and whose completion strikes human experience as a moment of revelation. Unlike the doctrines and axioms of science that pursue absolute evidence, artistic evidence is different, individual and constantly rediscovered. In repetition, renewal arises, for we are never completely done with works of art that captivate us, and rejoice in encountering them anew, just as each day commences with Eos' journey across the heavens at dawn.

The word photography was first used in the 1830’s. It is derived from two Greek words, photos “light” and graphein “to draw”: To draw with light. In Per Barclay’s photographs of installations, the inscription of light has literally found its place in anticipation of the photograph: A Chapel, a Boathouse, a Library: places that are temporarily marked by the reflection of light in mirrored surfaces. In the diptych Santa Caterina # 4 and Santa Caterina # 5, the church interior is inscribed in a surface of milk before the photographic recording, a process that is supposed to preserve the moment. However, Barclay’s photographs of reflections in a space question the notion of the permanence not only of the photograph, but of any image: the reflections in the temporary surfaces remind us of the fundamental premise of the image: that light inscribed on the retina is transformed into electronic information and processed in the brain into an image.

In the painting Chevrier assis, jouant de la flûte dans une clairière, a young shepherd is playing the flute in a clearing in the forest at dawn, while two lambs are cavorting in the foreground. The term clearing, clairière in French, implies that the picture does not primarily show a landscape, but thematises the origin of light: the morning is the day’s provenance. However, the artistic provenance of the painting is unknown. Corot was a popular artist of his time, and the painting on display in the exhibition is referred to in Stockholms Auktionsverket’s lot description as a copy belonging to the same period. The reference work with the same title is currently in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. Both paintings explicitly address the daily provenance of light, while the artistic provenance of the picture in the exhibition - despite the signature in the lower right-hand corner - remains anonymous and in obscure darkness.

In Angela de la Cruz’s Debris, a monochrome black canvas collapses around a bench, incorporating it into the actual physical darkness of the painting object. The work is characterised by the artist’s controlled destructive process in which the conventional materials of painting, often in combination with objects, are resurrected in new and unexpected formations. In his book Genesis (1982), philosopher Michel Serres writes about the eternally ongoing cosmic decomposition that sooner or later grinds everything into dust. De la Cruz’s work anticipates this fundamental and inevitable decomposition by recognising its earthly roots and bringing it under artistic control, halting the process for a moment and highlighting the painful beauty of ongoing decay.

Dag Erik Elgin's La Collection Moderne (Munch Starry Night) consists of the Munch painting’s original frame and a text painting identical in size to the work on display with the provenance formulated by the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles where the painting is located today. Starry Night was originally exchanged as a gift from Munch to Christian Krohg, and after being in the collection of Fridtjof Nansen, the painting belonged to the Andresen industrial family for three generations until it was sold to the Getty in 1984 by the Strand Corporation of Cayman Island via Aldis Browne Fine Arts Ltd. in New York. Starry Night’s provenance can be read as a paradigmatic example of the artwork’s journey in the 20th century from being a gift between artist colleagues to becoming an international financial asset, traded through the Cayman Island tax haven.

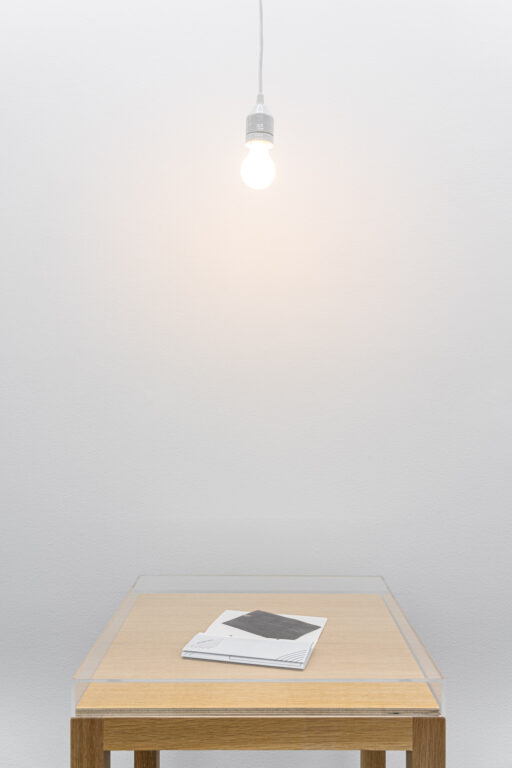

Ane Mette Hol’s working method unfolds in a correlation between process and content in which the subject is resurrected through repetition, whether it involves the repetitive scratching of the pencil, an exact doubling of the units from tape measure to drawing paper or the application of dry, white pastel chalk that evokes the characteristic surface of tissue paper. The phenomenon of light is a theme in several works, reflected in the tension between the repetition of the photocopy, the colour scheme of spectral analysis and the conscious handling of the destructive nature of light. In the exhibition, Untitled (The Beholder), a drawn version of a photograph in a wrapper, executed on light-sensitive paper, is presented in a display case under a lamplight that deliberately accelerates the inevitable movement towards destruction: An illuminated, microclimatic diorama that simultaneously highlights and reverses the work’s process of creation.

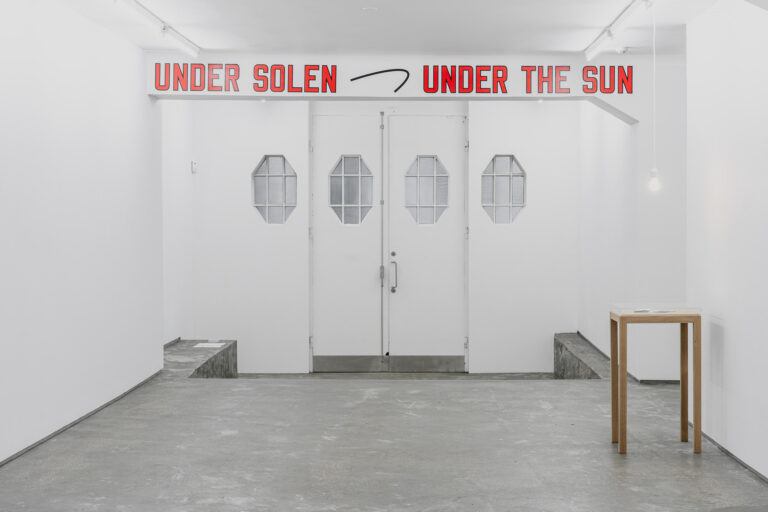

In line with the artist’s conceptual approach to sculpture, Lawrence Weiner’s work UNDER THE SUN appeals to the viewer’s imagination and co-responsibility in the creation of the artwork. The wall text points to a fundamental entity in the context of the exhibition: the sun as the original source of light and the prerequisite for all life that unfolds beneath it. But despite the sun’s crucial importance, its status as an ‘object’ is ambivalent: the sun is illuminating, but at the same time glaring, and potentially destructively blinding. Rather than viewing the sun directly, the spectator is therefore relegated to imagining it rather than establishing permanent eye contact with the sun as a physical object, a position that resonates with Weiner’s artistic programme.

Text by Dag Erik Elgin

Image: Christian Huygens’ (1629-1695) candle, representing the emitted light as superposition of spherical waves emanating from point sources in the source region