OSL contemporary is proud to present 'Feber' Vibeke Tandberg's fourth exhibition at the gallery.

Feber (Fever)

Text by Louise Jacobs

“Who am I? If this once I were to rely on a proverb, then perhaps everything would amount to knowing whom I ‘haunt’?” (Breton, trans. Howard, 1960, 11)

These are the opening lines of Andre Breton’s novel Nadja from 1928, an autobiographical novel about a random encounter with a mentally unstable woman. The woman Nadja became for Breton an example of the very essence of surrealism. According to Breton, the purpose of surreal art was to ventilate the subconscious so that the human being, in a state stripped of their outer shell, became visible. A so-called pure state for the surrealists was the triggering and active moment when reason became absent and the thoughts were devoid of any moral and ethical control—an automation controlled by uninhibited flow as an expression and analysis of the human mind. With this novel Breton moves out into a self study controlled by a type of flâneur philosophy, where the condition and the subject intertwine in a perpetual DNA spiral. As a protagonist in our own biological and existential prism, the question becomes A phenomenon worthy of a totem pole. There is no single unambiguous answer, the question makes up the answer in itself—it seems as though Breton is saying, and this elevates the question to a mutation of the surroundings, as a reaction to, and a repetition of, ourselves.

Vibeke Tandberg’s newest work is a sculpture series consisting of eighty-seven plaster cast busts of the artist herself. The sculptures all have individual expressions and different forms. Tandberg’s starting point is her own head and she has multiplied this through unique plaster casts using a plastic and flexible silicone form. The results are grotesque and beautiful variations of Tandberg’s own physiognomy and physique. Some of them look as though they are sickened by their own classical reference to the bust, while others seem proud to have travelled centuries from it and into their own axis of radical mimesis. A couple of them look as though they are in a sublime place between two dreams, while others have made a deal with death itself. Some are in ecstasy, others have found peace in gravitation, many look crazed, some just sad, while others are barely human, in a state reminiscent of a mixture of animals and human beings.

The liberation of the subconscious by surrealism releases mysteries that are exemplified through Breton’s Nadja. Who, or more precisely, what, is she? Vibeke Tandberg’s multitude of different versions of herself in twisted and misshapen hallucinatory, feverish conditions can be seen as a depiction of this tortured and crazed female figure who Breton romanticises—an action he describes as akin to trying to capture a wild animal. In this way, Breton emphasises Nadja’s ambiguous personality traits and leaves us with the question of whether this mentally unstable woman in all her contrary conditions could be the key to understanding art, and with it a deeper and more complex truth of who we are.

Even though Tandberg’s self-portraits in plaster use the bust from classical sculptural tradition as a starting point, they defy tradition and challenge recognition and identification. Idiosyncratic and individual traits that are not bound by representation or history make the sculptures into a chaotic landscape of human conditions. It can be read as a diagnosis of our feverish, pandemic times. And seen in connection with Nadja’s objectified subject and the surrealist doctrine of cultivating the uninhibited, there does not appear to be any authentic self in Tandberg’s feverish heads either. The many heads function, like Breton’s protagonist, both as a reservoir and a channel for understanding reality. Breton’s hunt for the liberated condition of the individual can also be recognised as a shadow in Tandberg’s sculptures, but without being able to get closer to an answer to the paradoxical question of who the I actually is. As Vibeke Tandberg herself writes in the essay “Uvilje”: “[...] the question in itself is idiotic, object and subject biting its own tail [...].”

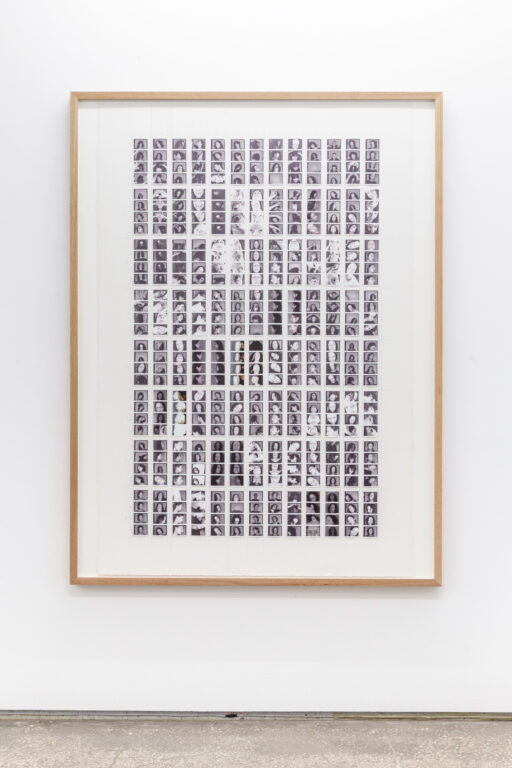

The plaster heads are also prototypes for many hundreds of photo booth pictures, laboriously glued to paper, numbered and framed to form large collages. And in Nadja’s mystical and mythical drawings that illustrate the novel, especially the drawing of the fabled chimera creature (made up of three animals: goat, lion, and dragon), Tandberg’s themes are recognisable as a study of psychological conditions or mythical animals that are archived and photographed in a photo booth in the mechanical way passport photos are taken. The ambiguous expression of the plaster heads, photographed from every possible angle, becomes an arena where the objects of reality and the photos of them meld together. As with mythical animals, the formal absurdity of Tandberg’s heads is inseparable from reality. Tandberg’s collages become a picture of a ransacking of the I, both the physiological and the inner one. It is like peeking into a kaleidoscope where the meticulous documentation seeks, just like humans, new conditions and new escalation of possibilities in a myopic ecstasy.

The originals of the sculpture series can be found on the pallets with newspapers, where Tandberg has printed the self portraits from the same photo booth, amounting to more than eighty-eight pages. Classical portrait postures, profiles, selfies; self depictions that are both beautiful and ugly; and at times abstract studies of the form of her own head and physiognomy spread out page by page in what looks like the world’s thickest tabloid paper.

The pandemic time we find ourselves in constitutes a dark backdrop to the surrealist self going in circles. Tandberg’s heads act as a decapitated chorus in a global feverish condition where the societal temperature has risen due to fear, anxiety and isolation. And where the heat branches out and spreads through an infectious uncertainty in a physical and geographic room where thoughts and questions about who we really are perspire without relational reverberation. «Real phenomenons in myself that I just have to be a tired witness to», Breton is said to have stated to the journal La Révolution surréaliste almost a hundred years ago. Maybe this was a description of the effect Nadja had on him. It sounds like an echo into the future of Tandberg’s exhibition Feber.